Review copy provided by Bigben Interactive. Reviewed on PC.

Avid readers of horror author H.P. Lovecraft would agree that it is extremely hard to capture the horror conveyed by his legendary stories. Their complexity makes them nearly impossible to translate. Developer Frogware’s The Sinking City tries to break these boundaries to create a dilapidated world plagued by terror and unspeakable monstrosities, but it fails to generate the atmosphere typical of Lovecraft’s fable, something that sets his work apart from every other type of horror.

There’s not much here to sing the praises of. The Sinking City‘s bleak world tries to reach the level of a Lovecraftian tale. But it forgets the most important ingredients of successful open-world games. As bleak as it may be, it also feels bland, rushed and ravaged by bugs and glitches. In some ways, it surpasses Call of Cthulhu but in many others, it falls far short. Its emptiness creates a sense of devastation, yet the sheer monotony of its amateurish game design and the banal narrative is far worse. It’s a bitter pill to swallow.

The game is set during the 1920s in the fictional city of Oakmont, Massachusetts. Charles W. Reed, a former navy veteran and private detective, is invited by the enigmatic Johannes van der Berg to a pier, determined to find out the cause of his nightmarish visions. The story begins suddenly. Not much is known about the protagonist’s past or why he became a private detective. For a private eye, he seems very aloof.

The mysterious, yellow-suited van Der Berg introduces you to the ill-fated city. Ever since the flood, the city has become ghastly, haunted by grotesque creatures called Wylebeasts. Van der Berg informs Reed about a person of interest called Robert Throgmorton who could help explain the source of his visions.

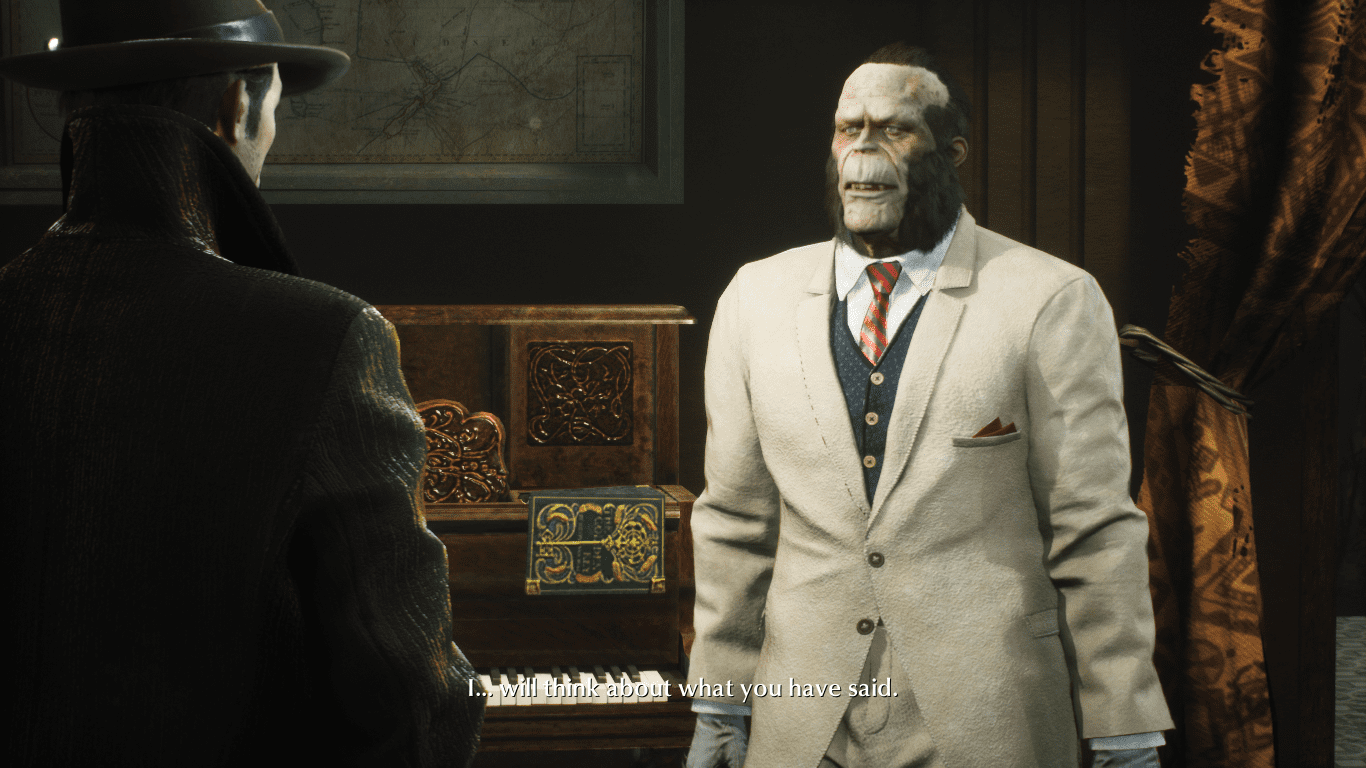

When Reed asks about a place to rest, van der Berg hands him the key to The Devil’s Reef. But the way to the port is blocked by the police and there’s no way around. Players find this out afterwards of course, for as soon as we approach the ape-faced man in the white suit, he makes it clear that no one is allowed to leave the port until his lost son is located.

As for who his son is, that remains a mystery until you interrogate him. The word Innsmouther (no explanation needed for those well acquainted with The Shadow over Innsmouth) surfaces quite often throughout the journey. Innsmouthers are people blessed by the sea. Their fish-like features separate them from the common crowd.

According to documents found throughout the game, Innsmouthers are excellent at fishing but loathed by the general population and especially by the ape-faced Throgmorton. We soon find out that Throgmorton’s son, Albert, took part in a deep-sea expedition funded by his father. After discovering that the newcomer (a word that’s frustratingly overused through the course of the game) is a private detective, Throgmorton hires him to find his missing son.

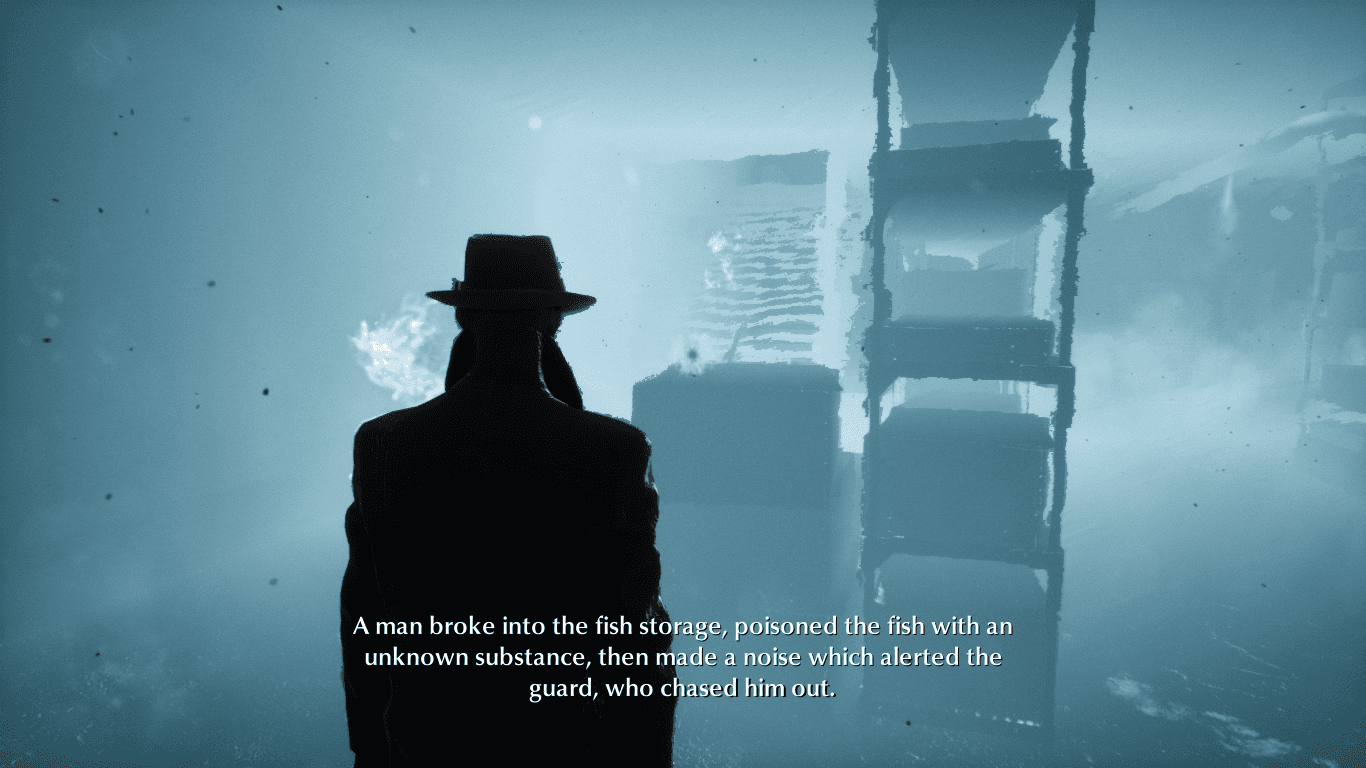

For some reason, his son Albert Throgmortan was picked up by a group of fishermen and brought into a ragtag establishment near the pier. Reed is sent to investigate the scene, although he’s not well-received by the policemen. The investigative procedure is quite simple. Players simply move the character around, interacting with specific objects. After touching a certain number of these, a rift appears.

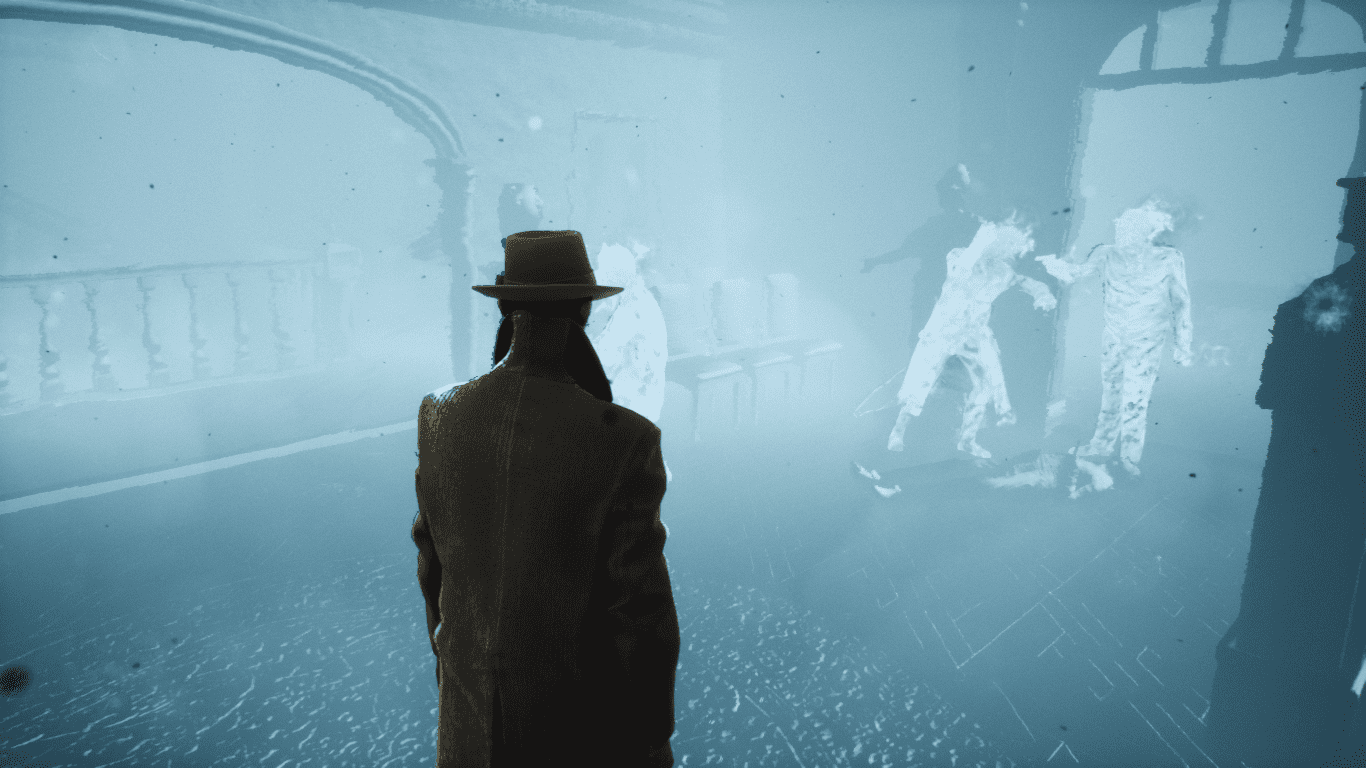

Entering this rift triggers a deductive sequence where players walk through a series of bluish blobs. Each of these blobs reveal incidents which occurred at the scene. All that’s left is to number them by walking close to the blob and pressing the left bumper. If the events are ordered correctly, the screen will flash green to show players they’ve made the correct assumptions.

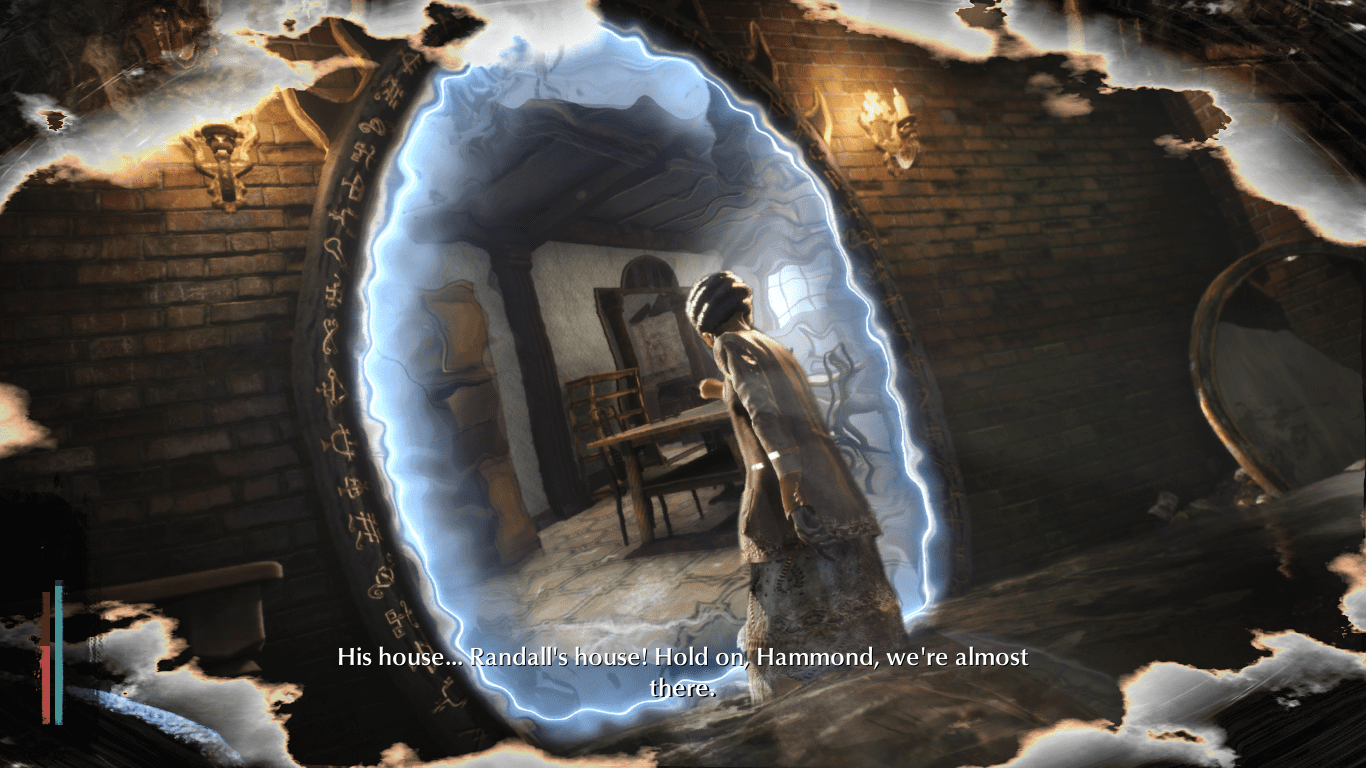

Charles is a bit too good with his deductions, so much so that he sees them not as conjecture but as certainty. In the late game, he goes as far as to even predict the name of the culprit without any mention of him in the crime scene. Is he a sorcerer? Well, perhaps he is, given that he can use his magical Mind’s Eye ability to trace people’s paths and uncover hidden artifacts which have been given a different shape. The magic is understandable, but his ability to see the past exactly as it was and to pick the names of people from thin air is disturbing.

After interrogating the fisherman Will Hammond, who is a witness to Albert’s disappearance, Charles finds out that some of his associates had indeed brought Throgmortan here unconscious and half-breathing. However, he seems to only remember so much, for after his friend Barry left to bring Robert, he put Albert in Lewis’s room. That’s all he could remember. After a further investigation, employing his magical abilities, he found out that Albert had attacked the group of fishermen under a mysterious, hysterical influence. The terror quickly spreads to the rest of the group.

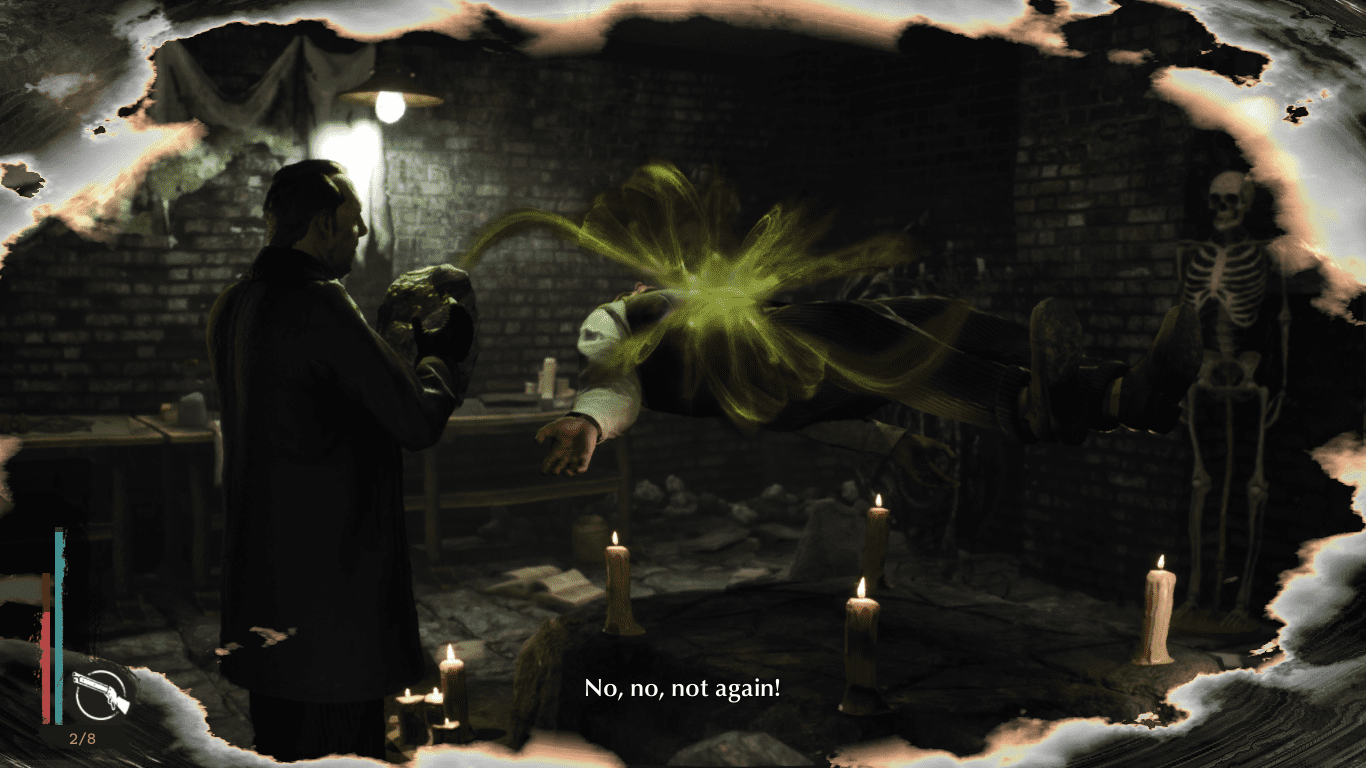

He got injured in the fight and Reed tracking a maimed but somehow incredibly strong Albert using the Mind’s Eye ability (the function of this ability will be explained later in the review) arrives upon a basement room. Inside, was the hanging corpse of the missing individual, son of Robert Throgmorton, shot in the head. It is there that Reed encounters the first harvester Stygian Wylebeast (monsterous enemy entities), which somehow doesn’t startle him at all. There is no fear in the tone of his voice, neither in his expressions or behaviour. In short, the acting is disastrous.

More importantly, who killed Albert? One of the fishermen? Is there any need for interrogation so he doesn’t go around making false assumptions? Of course not. Charles Reed is too good of a P.I. for that. He can deduce situations with his superpowers and come to conclusions at the drop of a hat. Why waste time questioning people and cross-examining evidence?

After that, the game enters a downward spiral. It turns into a machine that churns out random characters who can’t give you anything unless you do them a favour or two. It takes players around the whole city in a wild goose chase working double jobs. As it turns out, in the flooded city, everyone needs something.

When you’re following the main objective, the one or two characters who possess vital information that the players need will ask to provide additional tasks in return, which will annoyingly find its way into the main quest. It almost feels like the game should be called Quid Pro Quo (the name of a mission, humorously) and not The Sinking City. The “Sinking” bit is just a calculated smokescreen. Whatever mystery there is is killed off thanks to this ridiculous spin.

After the first mission players are quickly informed that the American dollar has lost its value in Oakmont and ever since the flood people have returned to bartering. But the game never elaborates why exchanging came to be favoured over currency. What it lacks is story depth. Its absence has left a confused and muddied narrative.

It’s not impossible to expect extra information from a game like this, but it destroyed a serious Lovecraftian environment with corny dialogue (especially Reed’s casual attitude when dealing with grave issues) and seldom a decent joke. In its defence, I’d say that the dialogues are well-paced, not too short to feel rushed and not too long to bore the players.

The game offers the illusion of choice. Like many games, it gives you a bundle of options to choose from— a system that’s appreciated. But these choices don’t have much of a bearing on the character, the world or the tasks that follow. There are different ways to complete a mission, and most of them seem to pose moral dilemmas.

You can choose to be the bad cop who’s always chasing after cash and betraying others or the good guy who puts people before a couple of bucks (with a few exceptions). But both of these end the game much the same way. There’s no real change to notice, no pissed off gangster at your doorstep because he’d found out that you lied to him. There are no long-term consequences at all.

Furthermore, there are no branching story paths. Instead, it gives three different endings to choose from in the final mission. The player will yet again be provided options which feels incredibly cheap since all the choices you made throughout the game have not made any noticeable change.

The Sinking City lacks a set of ramifications which would give weight to the choices players make, toss them around in hot water if they tried to be too cunning or bite their backs if they’re too good. It is lacking that punishment, that hardiness that would make the players pluck their hairs trying to choose from the stack.

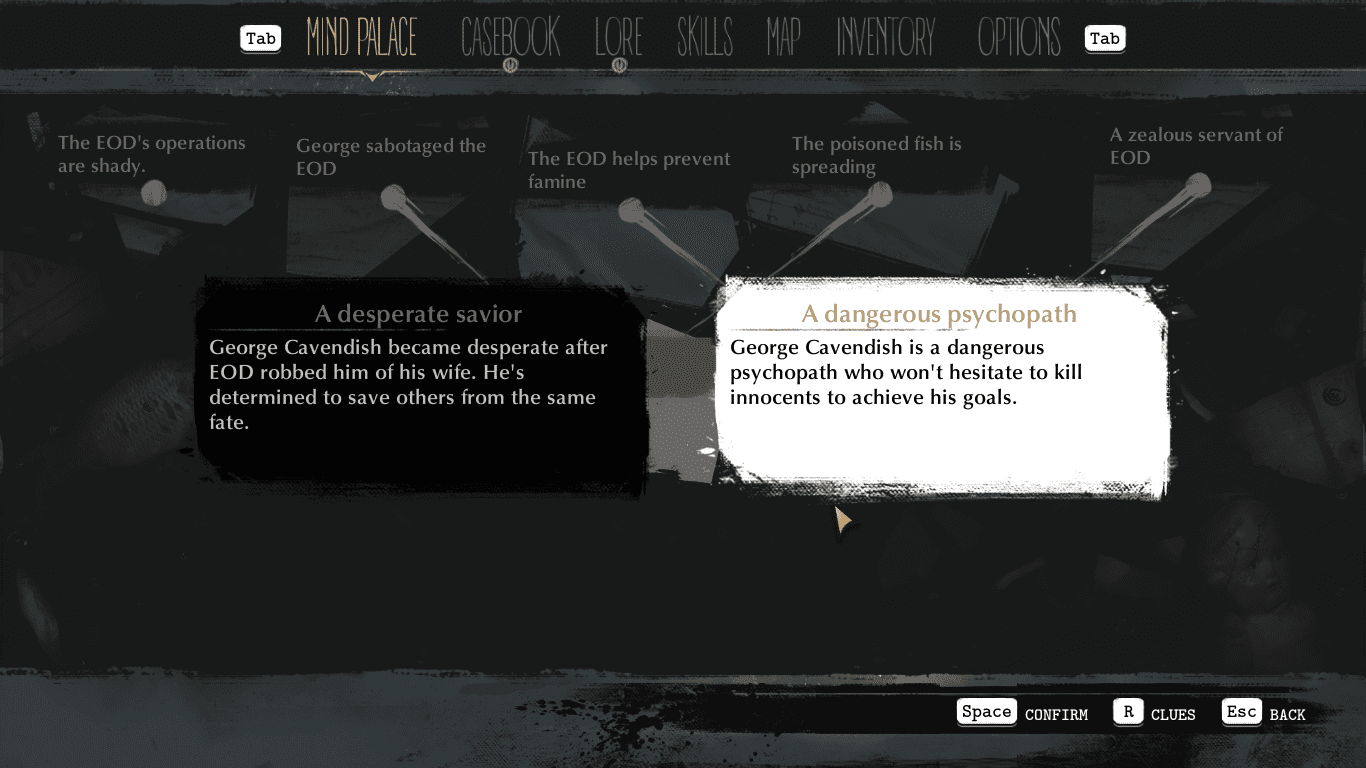

The Mind Palace is a system where players match information received in the course of the story to obtain a meaningful conclusion. But the matching process is more like random, rushed clicking and the decisions players reach fail to influence dialogue in any meaningful way. For example, if you choose to convict somebody in the Mind Palace, there are still options to acquit them in dialogue. It’s a convoluted mess, a bemusing info dump stripped out of Sherlock Holmes: Crimes and Punishments. There’s no point to it beyond some general exposition. It’s a useless feature, a watered-down rip-off that makes no sense.

Hallucinations are a big part of Lovecraftian horror. But instead of embracing the madness, The Sinking City shoves it to one side. Unlike Call of Cthulhu, it does not have any decent hallucination sequences, no puzzles to work through. Instead, it muddles whatever mood there was by switching to pre-rendered footage where the protagonist sees eerie visions.

The sanity feature is even worse. Whenever the meter falls, faded apparitions of monsters and a random doctor appear on the right-hand side of the screen. It’s not scary. The game also gives you a tool to plow through it: antipsychotic drugs. Hallucinations and visions are crucial in Lovecraftian tales, and it feels reasonable to expect antipsychotics in games inspired by Cthulhu mythos.

So the instant you become insane, you can bring out your trusty syringe, punch a hole in your flesh and voila! Never felt better. Instead of using sanity as leverage to enrich the atmosphere and make it dreadful instead of a drab walking simulator, the game gives you plenty of resources to fix the issue. Crafting is also useless. Instead of encouraging survival, it hands you plenty of resources to create stuff whenever you need to escape the clutches of death.

There is no difficulty or learning curve. You can easily craft health kits, antipsychotics and ammunition for every gun you have packed away. Although the game sometimes provides players with pre-made versions of these items, it mostly encourages them to stick with crafting. Not only does it fail to strike that essential balance between what items should be crafted and what items must be found, but also fails to make clear where and when some things should be crafted.

The combat, and especially the melee move, feels clunky. Enemy variety seems to be limited to a handful of beasts. The only one which frightened me was one of the largest Wylebeasts, modelled after the Elder Things from Lovecraft’s most popular novella At The Mountains of Madness. But with time, that fear vanished as well.

I found navigating the world of The Sinking City fascinating, and I enjoyed the way archives were placed in the game. Some information can be gathered from archives marked on the map. Police stations, City Hall, the hospital, the library and the Oakmont Chronicle newspaper are locations with archives where a range of data can be obtained. Navigation is interesting. Instead of placing map markers, the game gives a set of details for players to follow to reach their destination. Doors which can be opened are marked with the letter H.

There are certain areas infested with Wylebeasts and high-quality loot that I can’t understand the need for. Lovecraftian tales aren’t clichéd zombie games so why tread a path that’s so similar? The risk-reward system is not well-balanced. It gives players tons of loot, whether the enemy is robust and strong, or small and feeble. Traversal on the boat is redundant labor.

The watery lanes of the flooded districts invoke no sense of fear, nor are there any scripted instances where players fight aquatic monsters. Some missions that which required diving were similar. Occasionally, players fight wild sea creatures, but they can’t be killed, only stunned for a few seconds.

Even worse, there’s no return journey. When the mission concludes and you need to return, the game plays pre-rendered footage of the character activating a bunch of air balloons and rising through the deep sea. The difficulty is so low that the game becomes dull and uneventful.

“The Sinking city FEELS LIKE A DELIBERATE FAILURE.”

The Sinking City feels like a deliberate failure. There’s no sign of a struggle to overcome the challenges of game design and the game fails to innovate or feel unique. Trodding through this rotten world, which is wrought with imperfections, ravaged by age-old bugs and an atmosphere that fails to convey the horror it aims for. The Sinking City fails to look Call of Cthulhu in the eye, let alone match Lovecraft’s tales of fear and madness.