We live in times when the world is constantly changing. Certain things that would be considered unlawful and lead to punitive action fifty years ago are now considered fair and legal. But sometimes, prejudices persist in our psyche due to narratives being passed down generations so that it unconsciously affects our decision-making process.

In mass-media or its sub-groups, the film and the video-game industry, such biases have been the result of bitter controversies. Heated debates and public outrage regarding community representation and gender roles on social media platforms have railroaded modern companies to reconsider their PR strategies, have led new-gen filmmakers and game developers to switch to a more positive outlook to shape a more equitable society. Despite that, modern video games have been largely, or in most cases, partially devoid of the acceptance of racial minorities.

Kayode Shonibare-Lewis, game designer and game design lecturer at Uppsala University, Sweden, analysed the psychology behind racial biases through his presentation, 30 Black Characters: Reflections on Representation and Bias in Games and other Media, at a colourful, multicultural talk at A MAZE. Berlin on Thursday last week.

Bias comes in various forms

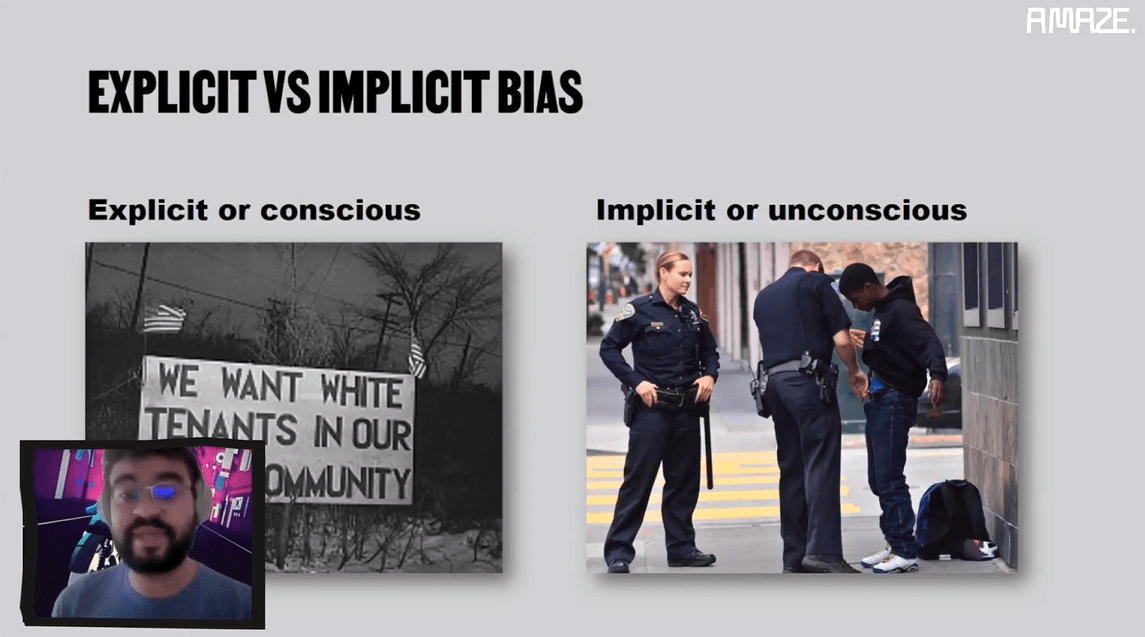

By bias, Kayode means a tendency to favour or disfavour specific ideas, objects, groups, etc based on our current understanding of the world. Moving beyond textbook definitions, he categorises bias as Explicit or Implicit — a somewhat Freudian observation of the subject. Explicit biases are conscious responses that are caused by irrational preconceptions held by people or groups of people. When these preconceptions manifest themselves in the physical domain unconsciously, they are implicit biases. To distinguish these two categories, Kayode employs images from Michigan in the early 1940s (a signboard intended to segregate whites from blacks) and present-day United States.

“In this image (img 1. – left) the people who put up that sign ‘WE WANT WHITE TENANTS IN OUR COMMUNITY’ know exactly what they want. They want segregation,” Kayode explains. “So, this I think is a sort of recognisable racism. This is when people were saying slurs and committing hate crimes and things like that. Then there’s implicit or unconscious bias. If you think of situations where somebody’s being called out for being racist and they have the response ‘I am not racist’, that’s likely because they were acting in implicit bias. Here, in this image (img 1. – right) you can see that the police are searching a black man, and black people are disproportionately searched by the police than white people. This is probably not because the police are explicitly thinking ‘I hate black people’ but there’s just an implicit bias that they are more likely to search black people than white people.”

The subject of representation

According to Kayode “representation is the depiction or portrayal of a person or group of people.” But this definition, in itself, is quite generalised and carries a broader meaning. By branching it into separate categories, a more localised and comprehensible meaning could be obtained. Kayode thus proposes two types of representation though he does mention that these may not be established terms.

“Accumulative representation,” he says, “is when we see an example of an individual from a group and the conceptual model of the possibilities of that group expands. So we update our bias about that group of people.” Using images of characters from the popular TV show The Simpsons, Kayode explains that the human brain identifies racial categories not just by colours but by the characters’ accents, dispositions and temperaments using established pre-existing stereotypes.

“In The Simpsons, if a character is yellow, they are white. We are not talking in terms of the colour white but in terms of the racial category white. When we watch The Simpsons we know that the yellow characters are supposed to be white. There’re are a lot of characters in The Simpsons and that’s why I chose The Simpsons to look at in particular. And here you can see that there are a lot of different ways of being a white person. This, of course, expands more broadly to the media in general. You get a lot of examples of what it can be like to be a white person and your bias about white people will continuously be updated accumulatively.

“On the flip side of the coin, there’s infrequent representation. It is when there are only a few examples of minority representation so that the few that do exist hold a disproportionate responsibility of representing that group. So if you go back to The Simpsons, a famous example of this is Hari Kondabolu’s documentary of the problem with Apu. If we take a look at Apu, his character is one of the few examples of Indian-American’s on television. Because there is such infrequent representation of Indian-Americans or any South Asian-Americans, you generally get compared to Apu, whereas if you are going to be compared to a white character in The Simpsons, if you’re a white person, you’re most likely going to be compared based on your personality, not just based on the nationality.”

How we perceive the world

Human beings normally perceive the world in terms of learning. Our minds are large caches of memory and as such the information we absorb is embedded there to be reflected upon later. Without adhering to exact psychological definitions, how one interprets the world is closely linked to three types of learning:

- Things that are learned through experience

- Things that are learned through second-hand accounts

- Things that are learned through mass-media and other mediums like books, magazines, radio, etc.

“Our biases are not necessarily fixed,” Kayode informs, “and so, they are developed from things that we’ve experienced and witnessed in our lives, things that we’ve been told generally by people that we know and similarly to things that we’ve been told. This is essentially being told things but through media; things that we see, read and play.

“So essentially what’s happening is that we see some representation that leads to our bias and then, as creators, if we are creating new characters our bias then leads back to the type of representation that we had experienced.” He suggests that the bias-representation conundrum is cyclical.

Kayode observes that this bias is not something that is limited to the white community but has seeped into the minds of coloured people as well. That is to say, existing stereotypes, that tend to be pervasive, have managed to invade the systems of those who are themselves the subject of bias, normally due to the media portraying coloured people and people of other ethnic groups in a particular manner.

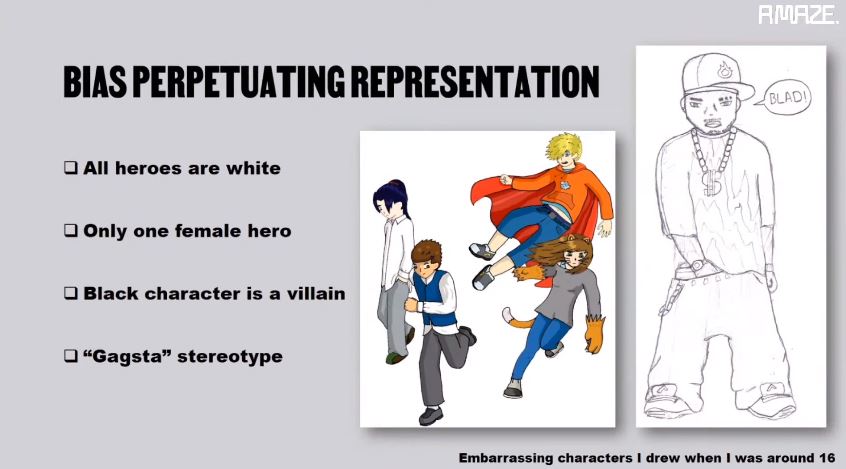

“I was working on a comic book with a friend who’s another mixed-race black British person and we were creating a superhero comic that we never finished but all of the main characters were white. The only black character we created in the comic book was the villain who’s also based on stereotypes of gangsters. And this wasn’t something that we questioned. This was just based on things that we’d consumed from media.

“We had three male heroes, one female hero. That ratio was something that we noticed in other things and even the idea that we were doing this because we’d noticed, it wasn’t something that we were reflecting on.”

Black lives matter & ‘30 Black Characters’ — looking at mass media

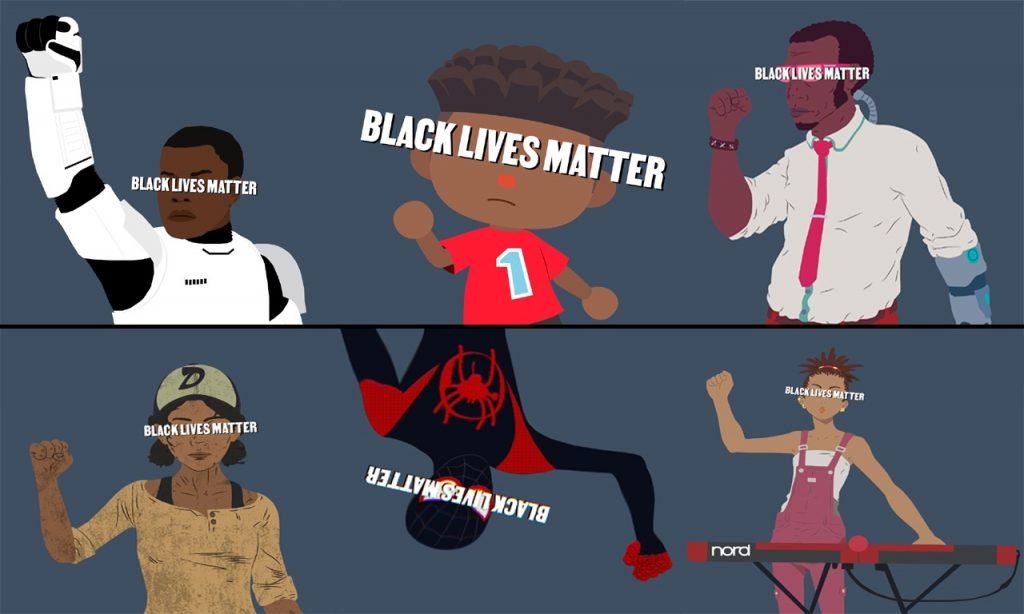

Following the events of May 25th, when an unarmed black man named George Floyd was brutally murdered by the police for trying to use a counterfeit bill, Kayode says that the response from various communities had most surprised him. He admits that the protests that sprang up in retaliation of police brutality from Minneapolis to Osaka had a lasting impact on him while he was stuck in Gotland. These “black issues and difficulties that minorities and people of colour face”, he says, would normally not be understood by those who don’t face such prejudices, but the huge amounts of white people that happened to come out in support of the protests had inspired him to draw thirty black characters from different TV shows, games, cartoons and movies as part of the #DrawingWhileBlack challenge that was trending on Twitter to oppose racism and racial bias.

“It was the beginning of the month and I had the idea to join the protest in my own way by going back and looking at characters from media that I enjoyed throughout my life, finding black characters and creating images of them joining in the protest. So, I mostly took characters from cartoons and games but I also took a few fictional characters from live-action shows as well.

“It’s kind of interesting to look at this in comparison to the image from The Simpsons with all of the characters together,” Kayode says while presenting an image of all the thirty black characters he drew. “It was actually quite difficult for me to find any examples of black characters, especially from games. There were a lot of games that I would’ve like to include but when I looked at them I realised there were no black characters in there at all. It meant that I had to do a little bit of a deep dive. I ended up going back into my childhood and taking characters from Tom & Jerry and Dumbo, things that I probably wouldn’t have thought of initially but were quite interesting to see how black characters had been depicted throughout my life.”

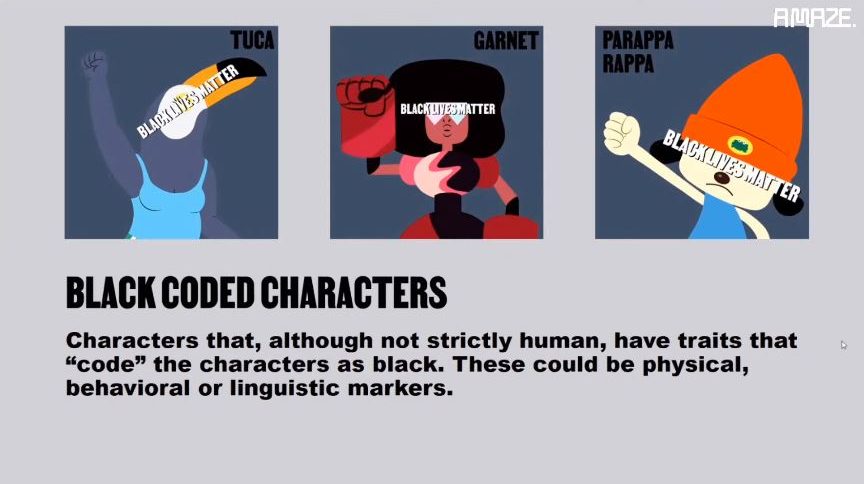

Kayode proceeds by introducing more methods of identifying various subsets of representation. According to him, the mass media often portrays characters of coloured origin indirectly, so that even when the characters are not being presented as humans, the audience would naturally associate them with a person of colour because of the way they act and talk. The underlying conditions that influence the audiences’ understanding in this particular manner are in fact governed by stereotypes. Alternatively, he claims, there are characters that have relied on racist stereotypes from history.

“These were generally characters that I noticed in older forms of media,” he confirms.

That certain characters like Mammy Two Shoes from Tom & Jerry, Mr Popo from Dragon Ball and Jim Crow from Disney’s Dumbo were originally drawn from racist historical sources is also a point that Kayode emphasised on. In the case of Mammy Two Shoes and Jim Crow, their names are based on certain stereotypes. The “mammy trope” was based on a racist archetype from the early 1900s when enslaved black women worked in white families as babysitters and caretakers. Jim Crow’s name arrives from the Jim Crow segregation laws that were in effect in the Southern United States till 1965. Likewise, Mr Popo’s character was inspired by minstrel shows and golliwogs. A third variety would be “tokens” or minority characters “that are included in shows with minimal effort as a nod towards diversity”.

“Token Black from South Park is named after this concept,” Kayode informs. “It is kind of a parody of it but they are generally side-characters. And I think this is also one of the side effects of infrequent representation. The character stands out not because of their characterisation but they stand out simply because of their race and being apart from the rest of the cast in the show.”

Black character in video games

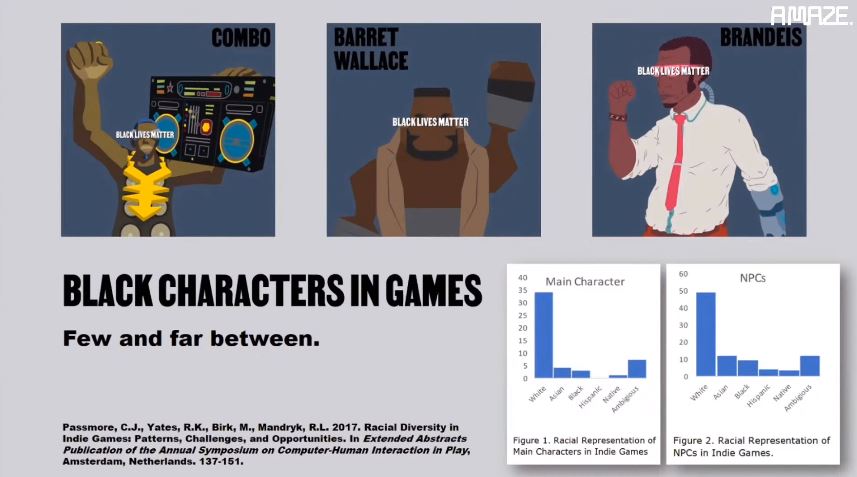

Given the bias, it is especially hard to find black characters in major video games. To think that indie developers would handle this issue more judiciously than their AAA counterparts would also be a misunderstanding. Kayode believes that this dearth of representation is even more profound in indie games. Citing a study published in Amsterdam, he suggests that diversity is an even bigger issue in smaller studios which overwhelmingly favour white people over racial minorities.

“One thing that games allow us to do is to create our own characters, and in the recent Animal Crossing: New Horizons, you’re finally allowed to create a black character with black hairstyles and dark skin tone. In previous games, there were quite a few convoluted ways that you have to do that if you wanted to be a black character.”

However, the fact that people of colour have to face opposition from others on the pretext of “baiting on social political issues”, over something as simple as character customisation in a game that’s about creating a virtual form of yourself came as a ridiculous argument to Kayode.

“The idea that that’s political is pretty frustrating to me, to be honest,” he continues. “Initially the only way that you could get a black character was to get a tan, which you could only do during the day time in summer months, and so it would take five days if you wanted to get the darkest skin tone and it was only temporary. After that, they did add a patch to the game where you could have a black ‘Mii mask’ but initially when they added that your arms were still white.”

The racial bias that dominates developers of games that have unfair character customisation may be due to a lack of foresight as to what the players want or why they would want to create a black character.

“Its less convoluted but its essentially giving a white character a tan in the character selection here,” Kayode says, pulling up an image of Pokémon Sun & Moon. “This is something that’s very common. It’s essentially just darker skin on the white character but not taking into account the difference in hair or facial features. They didn’t necessarily think about changing the colour of the mother in Pokémon Sun & Moon, but in the more recent games, you can see the mother’s colour updates.

“It’s not just in Japanese games, in Western games this issue of not being able to create black characters in character customisation exists. In World of Warcraft, they recently announced in the update that they were going to allow you to finally create different races for the humans. This update still isn’t out yet, and the game’s been out for a decade and a half. In The Sims community, there are black simmers who want more to the game, to add more skin tones and hairstyles.”

Minimising bias

Declaring that it is important to reduce bias, Kayode suggests that creators and game designers have to examine their own biases by “putting themselves in the players’ shoes” in order to understand what they will be doing and what they want. Near the end of his talk, he provides a list of things that could be used by developers to overcome bias in order to address the lack of representation in games and other forms of media:

- Accept that we have bias

- Practice questioning bias

- Learn about tropes/existing cultural biases

- Add this practice to your design toolkit

“I have specifically been talking about black representation here, but this goes across the board for people of colour in general or people with disabilities and LGBTQ representation. We all have biases about people in other groups but also about our own groups and I think, generally, it’s a good practice to question those.”

If we talk about biases, as an eastern european, im tired of being lumped in the same boat with western european colonial grievances when it comes to progressive activists, POC’s including, just because i share the same skin color with the british, french etc. My people didnt own colonies nor african slaves, we were colonized ourselves by germans, swedes and russians. Stop treating whiteness as a monolith, as its racially prejudiced in on itself.

I agree, Janis. You make a very good point. Whiteness being treated as a monolith is, in itself, is a bias. Everyone has bias to some degree, as Kayode says himself. But at the same time, we cannot simply ignore the abuse faced by people of colour for generations. My people were colonised and treated differently just because of their colour by the Brits. We are all in the same boat here.

No we are definitely not. Like… you just justified being a bigot for past suffereings you have never lived.

Is oppression inherited through DNA? Until you show proof of that, just stop generlizing white people.